Things are going from bad to worse for the economy thanks to 12 brutal rate rises and skyrocketing inflation – and it could take years to fix.

Upon the release of the latest UK inflation data, Britain became the cautionary tale for the RBA and central banks around the world.

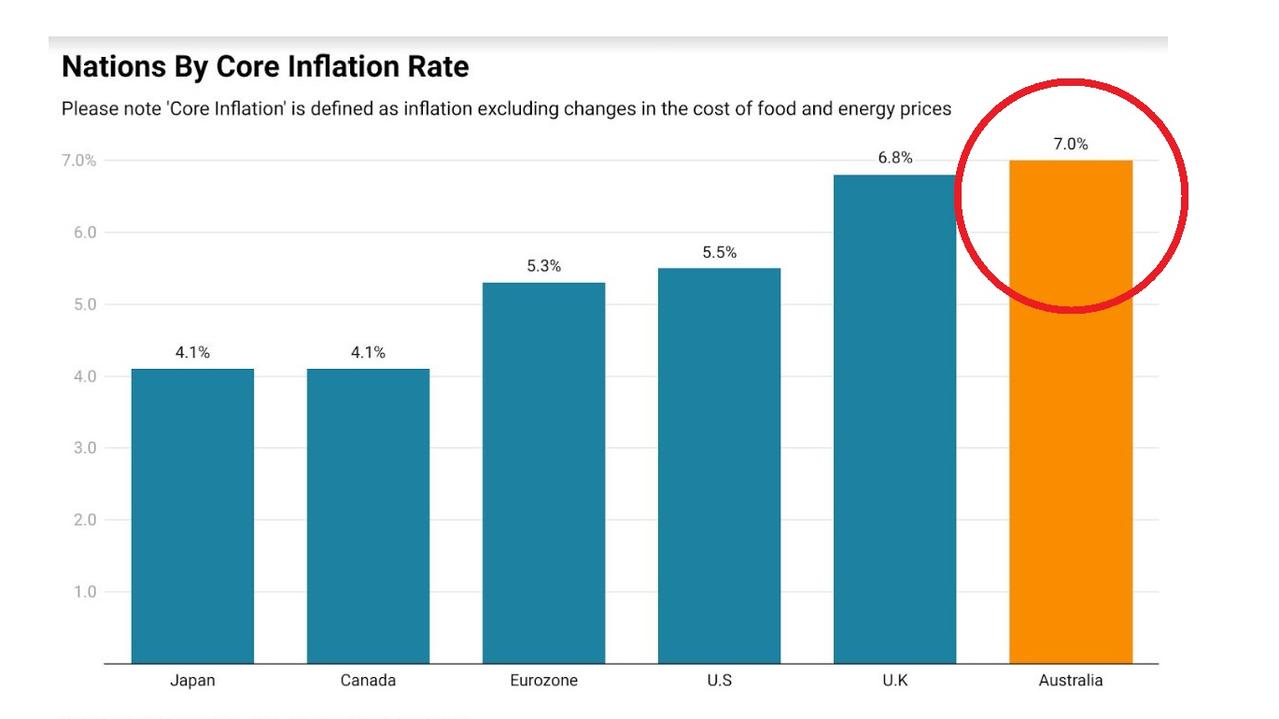

It revealed that core inflation (inflation excluding food and energy) in Britain rose to a 31-year high of 6.8 per cent, 0.5 per cent higher than the previous peak in 2022 recorded back in October last year.

Despite the Bank of England raising interest rates 12 times from 0.1 per cent in December 2021 to 4.5 per cent following the latest rates meeting, inflation in the UK has only become more and more entrenched.

With inflation now confirmed as sticky, financial markets have priced in further rate hikes by the Bank of England, pencilling in a further 0.75 per cent in rate rises before the end of the year.

In recent months, Britain has seen the most widespread strike actions by workers since the early 1980s, as workers come together to press for pay rises that better reflect the rapid rise in the cost of living.

With minimal signs that underlying inflationary pressures will come down swiftly, workers are less likely to accept pay deals that insufficiently reflect inflation’s persistence, incentivising them to ask for larger wage rises, if only to keep up with inflation.

For central banks around the world including our Reserve Bank, the Bank of England’s path is now a guide in what not to do, while also acting as a warning that if inflation becomes entrenched it can become self-enforcing, even after the initial shock that may have created it has passed.

The RBA raised interest rates on Tuesday for the 12th time since the rate rise cycle began back in May of last year. Picture: NCA NewsWire/Martin Ollman

Australia by comparison

Meanwhile, by contrast in our own backyard, core inflation is 7.0 per cent, but down from its 7.8 per cent peak in the December quarter of last year.

But while core inflation is the Bank of England’s preferred inflation metric and allows us a ballpark comparison with the UK’s experience of inflation, it’s not the one the RBA put the most stock in.

For the economic boffins at Martin Place, the preferred inflation metric is the trimmed mean, which strips out the volatile items, the top 15 per cent and the bottom 15 per cent, in an attempt to get a better picture of how broader inflationary pressures are performing.

On this metric, Australia’s progress compared with the UK and other nations has been less favourable.

Since peaking in the December quarter of last year, it has declined from 6.9 per cent to 6.6 per cent. Positive progress to be sure, but a long way away from showing a reasonably swift path back toward the RBA’s 2 per cent to 3 per cent inflation target range.

It’s worth noting that in the past 30 years the trimmed mean rate has spent the vast majority of the time at or below 3 per cent, with the only major exception being when it rose to a peak of 4.8 per cent in the run up to the global financial crisis meltdown.

In our own backyard, core inflation is 7.0 per cent. Picture: Supplied

The RBA is in quite a tight spot

In the words of Treasurer Jim Chalmers earlier this week, “inflation is more persistent in the economy than any of us would like”. And this was reflected by the RBA’s move to raise interest rates on Tuesday for the 12th time since the rate rise cycle began back in May of last year.

Amid a resurgent housing market and the largest increase in the minimum wage since 1990, the RBA appears to be increasingly concerned that inflation could remain uncomfortably high for significantly longer than it initially anticipated.

There will also be the added inflationary pressure that will come in the form of the Stage 3 tax cuts in July 2024. According to figures from the Parliamentary Budget Office, the tax cuts will add over $20 billion a year to the pockets of households set to receive them.

To put that figure into perspective, if we were to assume that all mortgage holders were fully impacted by a change in monetary policy, it would be the equivalent of the RBA cutting interest rates by around 1 per cent.

Once the reality of households already paying higher rates, increases in bank deposit rates and borrowers well ahead on their mortgages is factored in, the impact would be significantly greater than 1 per cent cut in interest rates.

RBA Governor Phil Lowe also noted recently that there was still a great deal of rental inflation that had not yet fed into the consumer price index.

According to data from the ABS, rental inflation is currently running at 4.9 per cent year on year. The RBA anticipates that rental inflation will peak at around 10 per cent.

Due to the lag between asking rents and rents as measured by the ABS, rental inflation is likely to remain extremely high for quite some time.

Looking ahead

With warnings from the RBA that further rate rises may lay ahead, the ongoing tightening of monetary policy is a double-edged sword.

On one hand, it will bring down inflation in time, but on the other, it’s increasingly likely to cause a recession to do so.

Governor Lowe and the RBA call the path ahead in which Australia manages to avoid a recession a “narrow” one.

While the potential paths ahead for the Australian economy may be challenging, relative to the UK, Australia is in a much better position.

Underlying inflation is coming down, albeit more slowly than policymakers would like, while in the UK it just recorded a new multi-decade high.

As events continue to unfold, the window in which the current inflationary cycle ends positively for the broader Australian economy is rapidly closing.

But ultimately, even if somehow Australia manages to avoid a technical recession, the damage has already been done in many ways.

Since high inflation reared its ugly head in Australia once more, 14 years of real wages growth has been destroyed and at the rate of real wages growth seen prior to the pandemic, it could take decades to get it back.

Leave a Reply